As one enters the compounds of Nandan - the administrative building of Kala Bhavana, one comes across on the right, a free-standing 'wall', which, while being significant in proportion is quite non-intrusive in its repose. Bearing variable, asymmetrical vertical folds, this accordion-like structure segregates the two spaces of admins and creation. Resembling red sand stone, the cement-cast wall is not obstructive enough to stop one; it only proposes a temporary halt, a gentle musical interlude, as it were. Like a piece of folded origami resting on the gravelly grounds, its eastern face offers up vertical triangular projections. The back is flat, broken by vertical grooves of corresponding variable widths. There seems to be some kind of a rhythm in the asymmetry of the folds and grooves, some sort of subtle progression that impinges upon one's senses like the notes of music.

Facing the accordion wall, further east, to the left of the entrance gate, one finds a similarly coloured cylindrical column rising out of the laterite garden. Running up its height there are multiple loti-form depressions - as though scalloped out with a knife - their reciprocal intervals contracting and expanding, like the opening and closing of petals, or perhaps like the reeds of a flute. Once again, here, one is made conscious of the rhythmic progression in the relative proportions of the expansions and contractions; the 1:2:3 ratio playing out in the sequence of 123 231 312, in precise vertical echo to the accordion wall.

Beyond this column are strewn about some smaller forms, like minor notes, reclaiming an otherwise flat ground. One encounters what appears to be a horizontal half-note of the accordion-wall, and then, still inflecting the landscape, a small unit of the vertical column - together, like mutually inverted echoes - before one's vision fades away towards the east.

This whole ensemble constitutes a single work, 'Opposite'; sculptor Sushen Ghosh's interjection into the architectural environment of Santiniketan, conceived in the mid- late 1970s and executed into the 1980s. At a glance - stand-alone pieces - that are but interdependent units in muted interaction with each other, like two people whispering across a river or road; here, the passageway to the steps of Nandan. And, through the course of a day, it is an experience to observe the sunlight sliding down the crisp creases of the accordion or lingering through the soft recesses of the flute-like pillar, making silent music.

****

What is fascinating about Sushen Ghosh's work is the fact that the apparently quite straightforward objects - objects that could be called abstractions - demand a cognitive reshuffle and leave one with the scope of talking about their contexts, surroundings, attitude and of course, the forms. This almost makes room for narratives. Thus, for Ghosh, the horse is not a representation, it is the hoof, which by repetition creates a force-field, hence occupying the entire field of vision. It is as if the artist has worked to create or capture a circumstance of experience or freeze a phenomenon.

Sushen Ghosh's earliest exposure to the sculptural form was in his childhood, through the idol-making he witnessed during the festivals in his hometown in Silchar, in the Sylhet district in pre-partition India. His introduction to the sculptural language took place during his student days in Santiniketan, under the tutelage of Ramkinkar Baij, among others.

Sushen Ghosh with his sculpture of Ramkinkar Baij, his teacher and mentor.

Sushen Ghosh with his sculpture of Ramkinkar Baij, his teacher and mentor.

Paradoxical as it may seem, despite the overall figurative and representational tradition of Santiniketan, Ghosh attributed his eventual genesis into an abstractionist to the pedagogy of the very place. At the time, Santiniketan was quite in benign touch with nature. There was a sense of freedom and informality in the spirit and quality of educational instruction. Learning in Kala Bhavana was less about acquiring the formal skills of representation and more about cultivating clarity of vision for identifying the underlying energies of things; the rhythms, the pauses and flows, the structures and movements, the similarities and dissimilarities. It was about learning the principles of the abstract language of art. Simultaneously, the craft and design traditions of Santiniketan also shaped the aesthetics. Ramkinkar Baij, who was Ghosh's primary mentor, had the innate ability to absorb the essences of form and adapt international sculptural idioms to contexts relevant to the local. He was a master of representation - successfully bridging the gap between reality and metaphor in his abstract experiments. Fortunately for Ghosh, Baij was then in the most mature period of his career as a sculptor and was accommodative in his mentorship. In his own foray into abstraction, no doubt Ghosh was inspired by the latter's example and indulged by the master to play to his selective affinities in his formalist quest.

He was able to grasp the essence of phenomena and transform them into new configurations, often translated through his musical sensibilities. Music comprises components such as rhythm, harmony, consonance, dissonance and many more factors that make a composition possible. It would not be incorrect to assume that Rabindranath Tagore, in founding the Kala and Sangeet Bhavanas together, might have envisioned a mutually informed contiguity. An accomplished flautist himself, Ghosh's passion for music and knowledge of musical tropes found expression in his approach to the abstract form. He is often quoted to have referred to his sculptures as 'Frozen Music', perhaps borrowing from Goethe's popular reference to architecture.

****

In 1970, Sushen Ghosh had the opportunity to travel to England for study at Goldsmiths College. This enabled him to observe European modern art and specifically, abstract art at close proximity. He was able to meet some of his favourite sculptors, like Henri Moore, Kenneth Armitage, Barbara Hepworth, who were all still practicing at the time. He was introduced to the concept of the sculptural form as a product of orchestrated mathematical application or geometric progressions and to sculpture as a modular construct - no doubt, also, to the work of older artists like Brancusi. Indubitably, a landmark experience in his journey of abstraction that proved an inspiration in his formal pursuit of the geometric form.

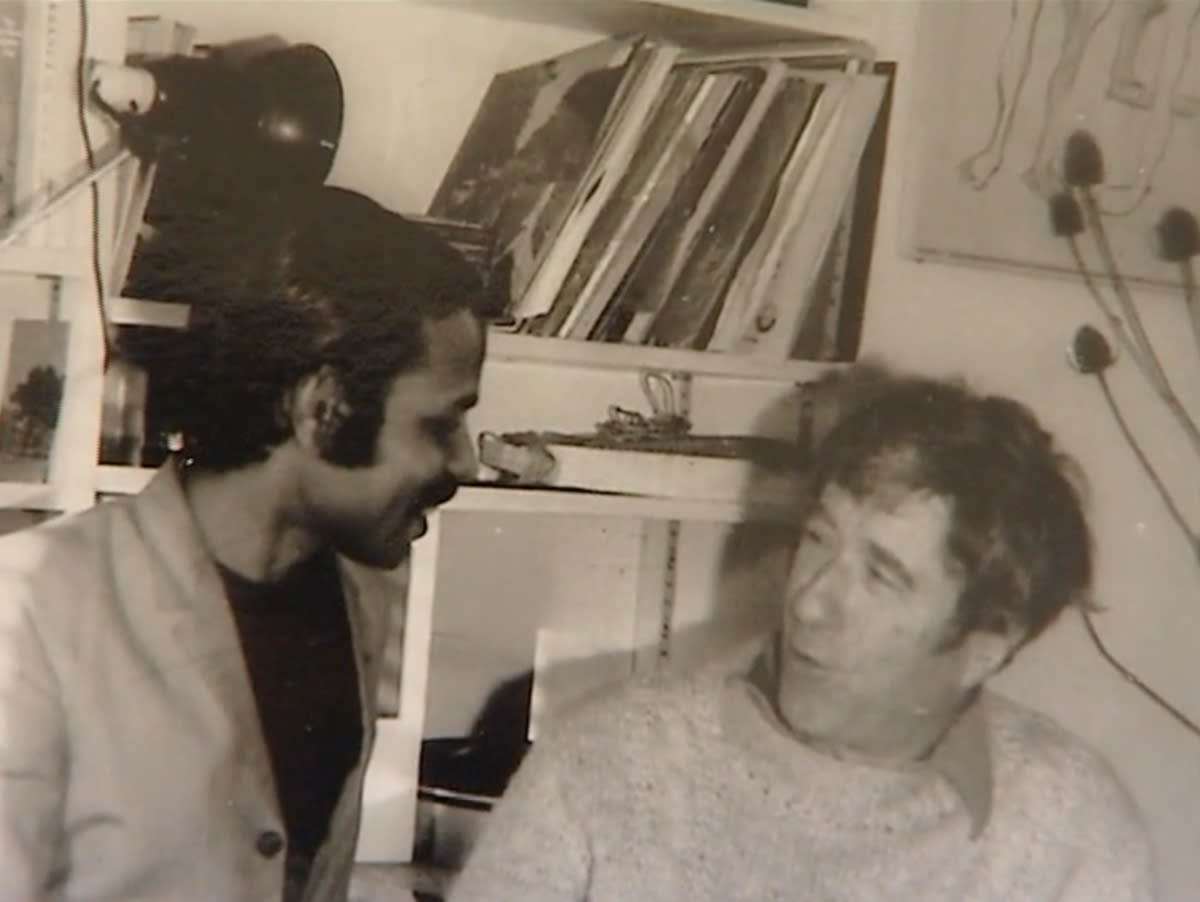

Sushen Ghosh in conversation with Kenneth Armitage, 1970.

Sushen Ghosh in conversation with Kenneth Armitage, 1970.

It is believed that the self-consciously abstract artist has a subconscious perception of threat from the technologically modern world, because it is constantly in flux; the sense of permanence is seen lost, along with the sense of assurance of the superior values of pure abstraction. Ghosh, however, was exempt from this anxiety, as he did not make a very clear distinction between the modern and the traditional. His pursuit of abstraction was more organic and grounded in tradition. Abstraction was not an end in itself for Ghosh, it was the means to architectural, mathematical, lyrical, rhythmic, or even philosophical explorations. In a sense, he was an eclectic.

****

Ghosh's sculptural architectonics, as in evidence in Kala Bhavana, is often based on rhythmic syncopation and containment, or harmonious cohabitation of units. What appear to be casually and randomly resting pieces have been measured, with placements and positions carefully determined in accordance with an unseen ratio. Mathematical calculations, deliberate rhythms to achieve lyrical ends.

Sushen Ghosh, Composition 1:2:3:4 (Set of 8), Bronze,15 x 30 x 30 inches, 1990-95.

Sushen Ghosh, Composition 1:2:3:4 (Set of 8), Bronze,15 x 30 x 30 inches, 1990-95.

Rhythm is a translatable metaphor, it can be transferred from poetry to music and vice versa, it can be extended to drawings and to life at large; it can thus escape clock-time linearity. Modular rhythm is contained, like architecture, like product design, before it is released for usage. In Sushen Ghosh's sculptures, the modular rhythm expands and contracts according to the project. In quasi-figurative and semi-referential works, the rhythm is Vitruvian, following renaissance or perhaps le Corbusier. In the works where he shuns reference, Ghosh follows the rhythmic relation parallel to that of music. Thus, music, architecture and the human body bond in a singularity of contrapuntal world rhythm.

There are some drawings and three groups of sculptures in the current exhibition. One set of forms has referential and descriptive quality to it. The second type consists of geometric configurations and forms that resemble interlinked puzzles or mazes. The third group of works appear to be smaller versions of ambitious modular architectonic projects, similar to the outdoor ensemble on the Kala Bhavana premises.

Lyric, Still, Sculptures by Sushen Ghosh, Installation View at Project 88, 2023.

Lyric, Still, Sculptures by Sushen Ghosh, Installation View at Project 88, 2023.

Some of the forms are seemingly double coded, such as the constructivist figure of a man with raised hands that could be the gesture of a man travelling through the troubled states of north-east India, where a sudden, body-search at every important juncture had become the norm at one point of time. It could also have more benign connotation, transcending religious boundaries; it could be a man performing the Ajaan prayers or performing a kirtan, lifted chin pointed up at the sky, apparently resembling the prayer metaphor. Another figure is seated, with what appears to be truncated legs and a disturbingly truncated head. It might be a figure symbolic of some terrible violence, or it could be a figure that is converted into a receiving vessel- a receptacle of flowing grace or anything nature has to offer.

Sushen Ghosh, Elevated (Vertical), Bronze, 32 x 7 x 4.5 inches, 1970-75.

Sushen Ghosh, Elevated (Vertical), Bronze, 32 x 7 x 4.5 inches, 1970-75.

The group of sculptures that resemble mazes or puzzles, is an experiment in establishing ready-to-use modules, such as the rules of equilateral triangles or a series of concentric shapes, which produce the illusion of a maze upon repeating the course of action.

An ancillary to Ghosh's out-door sculptures form a third set, where various forms derived from traditional objects are sliced or altered in some manner and rearranged in rhythmic progression. One such piece is a pitcher that has been sliced and then spliced together in a stagger, so as to form an incomplete circle, indicating the possibilities of combinations as in musical notes. Often, the same forms perform an act of multi-stablity, indicating multiple meanings in their combinations. The same rhythm then plays out in another set of objects resembling truncated stems in its various states of tropism.

Sushen Ghosh, Change of Moods (Set of 8), Bronze, 8 x 4 ft (approx), 2011

Sushen Ghosh, Change of Moods (Set of 8), Bronze, 8 x 4 ft (approx), 2011

Whenever presented with the occasion, Sushen Ghosh has utilized the outdoor spaces to gently introduce his architectonic extensions and syncopations. The modular composition in front of Nandan is followed by a configuration of evenly distributed asymmetrical units near Sangeet Bhavana. For a time, this work lay awaiting its turn for realisation into a larger scale, in the form of a terracotta maquette. Finally, it was installed in a space where some date palm trees had been standing a few years ago, their lopping-off perhaps necessitated by a newly constructed hall. Ghosh observed the rhythm in the palm tree to recur in the ratio of 1:2:3; 2:3:1; 3:1:2, and conceived a set of vertical units, each marking the characteristic rhythm in alternating sections twisted at right angles to the preceding ones. These make the eyes go up and come down, like the experience of climbing up and coming down the palm tree - 'aaroha' and 'avaroha', the terms used in Indian classical music - indicating notes of ascending and descending arrangements.

The artist with his large- scale sculptural iteration of Composition 1:2:3:4 at Shantiniketan

The artist with his large- scale sculptural iteration of Composition 1:2:3:4 at Shantiniketan

Like the opening 'aalap' (prelude) to any classical music, lyricality rehearses itself in a variety of rhythmic forms, Sushen Ghosh captures them, as if in a frozen moment, where movement remains always a form potential energy.