If limits signal a hostile boundary – or a presumed end – of material or thought, why approach it? And at this concrete edge, what can you even find? Sandeep Mukherjee taps into an unusual but uncanny impulse from the very onset of this exhibition, wherein a deliberately orchestrated atmosphere unsettles your gaze. From afar, antagonistic structures are juxtaposed against one another, but as you move closer, these material antipodes (pushed to their extreme edges) stage the necessary contradictions that make (and unmake) our perceptual realities. The limit is not transcended nor does it collapse; for Mukherjee doesn’t fathom escapist pathways, rather, he compels viewers to “think through the end limits of our [human] condition.” [1]

As you enter, five large site-specific paintings allude to baroque and cosmic forms – an exuberance contained within precise frames; but across the next wall, six raw, depleted skin-like aluminium panels are suspended from above, a visual unnervingly similar to an encroaching slaughterhouse. In yet another corner of the gallery, futurist geometric patterns pierce through painterly surfaces with a surreal luminosity. These life-sized sculptural forms and acrylic paintings are typical of Mukherjee’s oeuvre, wherein an immersive experience is an integral component of the artwork itself. Whereas each artwork contrasts the other, all remain anchored within a singular approach towards abstraction and movement: a kinetic method that defines Mukherjee’s probe into the conceptual apparatus of a ‘limit’ in our contemporary. Moreover, by exhuming the finite borders of our perception, Mukherjee reframes perennial questions on the tenuous relation between the human and non-human in the face of immanent entropy.

For Mukherjee, abstraction becomes the visual key to unravel a radical potential within the extreme edges of material, thought, and time. Contemporary abstraction presents a plenitude of (seemingly disparate) visual forms, histories and methods, conceived for a distinct purpose: be it spiritual, gestural, symbolic, structural, or minimal. Yet with each renewed iteration, one question remains: why abstract our reality? Or put differently, how does abstraction continue to serve us today? Far too often the ‘abstract’ is presupposed as a portal to transcend lived reality – and exist independently – by unlocking a fantastical realm of infinite, unlimited subjective possibilities. However, in this show, Sandeep moves in the opposite direction: with finite boundaries, precise edges, and contrasting textures, his abstraction approaches ‘limits’ from oscillating vantage points. These palpable (and pulsating) borders of materiality and meaning morph into unexpected sources of desire, wonder, and uncertainty; as such, Mukherjee’s abstracted surfaces rediscover the ways in which we comprehend ‘limits’ themselves.

I. Limits of Vision

What begins as a spectacle – an immersive encounter – soon demands an intimate reading. In Mukherjee’s world, objects are not what they appear to be. He carefully deconstructs and re-arranges our visual perception in two ways: first, by conjuring blind spots within your line of sight, and second, by incorporating movement (a recoil of sorts) into our ways of seeing. For Mukherjee, abstraction is no longer a noun – a site, an aesthetic, or a style – but transforms into a verb. He draws on the kinetic by slicing flowing matter in order to highlight a particular aspect of that flow. This movement allows the artist to approach different perspectives (and materials) in order to render the previously invisible, and at the same time, recognises the limits of each perspective.

There’s a fleeting retraction, an act of pulling away at the corner of each work; cosmic forms both emerge and recoil. From afar, his precise geometric forms allude to hard-edge abstract painting from the 1960s – coined by art critic Jules Langsner – that referred to artists along the West Coast, where incidentally, Mukherjee currently resides. Langsner delimited bold autonomous shapes, rigid yet saturated colour fields, as it gathered to form a singularity within the historical continuum of geometric abstraction. But as you go closer, for instance in Echo, such finite forms suddenly expand – Mukherjee’s surfaces then erode with gestural excesses, each diffracting light to breathe a space of its own. Whereas a birds-eye view indexes geometric modern constraint, a closer lens exposes expressionist textures and layers. This ceaseless contradiction – to recede yet erupt simultaneously – forms the crux of Mukherjee’s kinetic approach. Situated at the very edge of the gestural and geometric canon, Mukherjee distils a nuanced visual vocabulary of his own, where to move is to see differently.

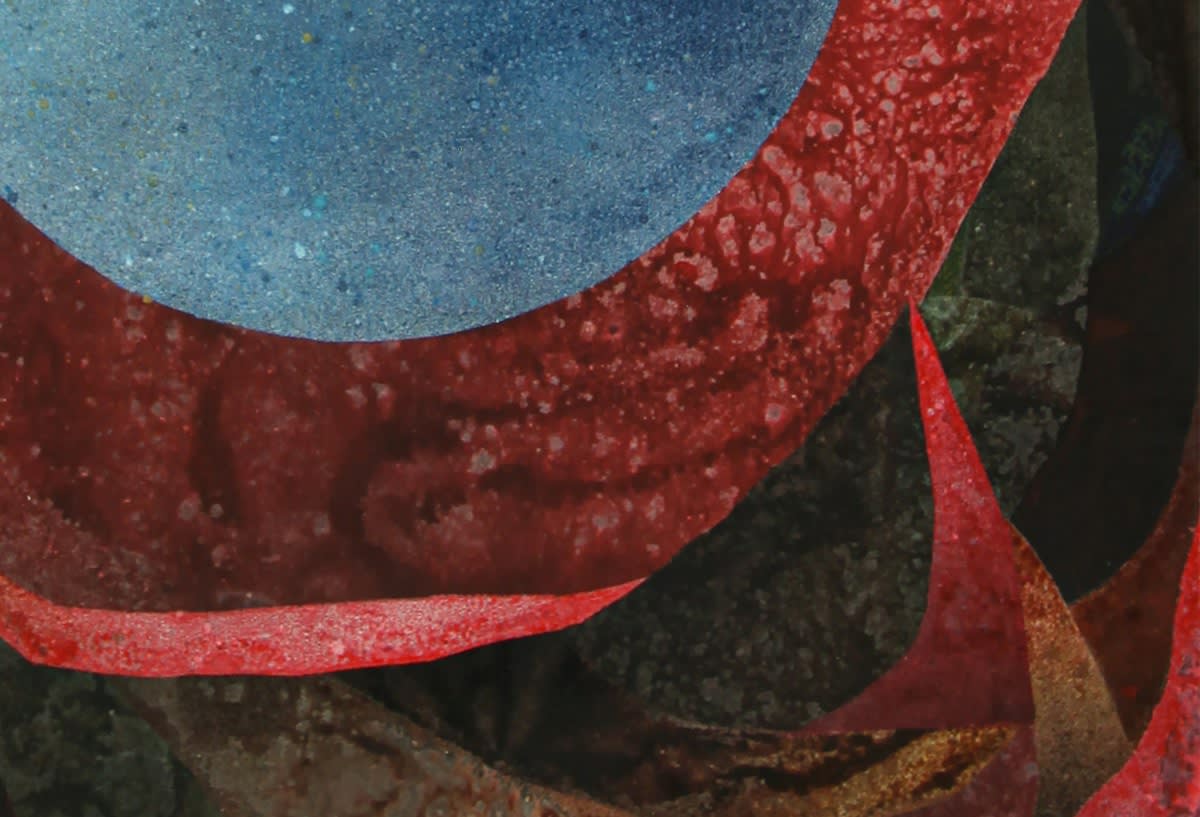

As the title suggests, Mukherjee’s Parallax series occupies the liminal edgy space between two distinct vantage points; ‘parallax’ refers to the difference that a viewer perceives when looking at an object from two separate points of view. Composed of 5 large acrylic paintings on Duralene, Parallax probes the duality between our microscopic vision and a birds-eye view from afar. Here, haunting red and brown hues resemble leaves or thorns in a forest, perhaps even on the brink of flames. Yet at the same time, a receding cosmic blue sphere captures your gaze, evoking a different viewing point, one from a surreal distance outside our horizon. The tension between the dual viewing points is palpable; time collapses but movement does not.

Sandeep Mukherjee, Parallax, Detail , Acrylic and acrylic ink on Duralene, 84 x 60 inches, 2022

The earthy splinters strive to grasp the oscillating blue sphere, a movement that erodes from one painting into the next. Nevertheless, the inflamed thorns become an asymptote – for the sphere remains permanently within their line of sight, but always out of reach as you approach it. These layered textures of acrylic took form over the period of eight years; Mukherjee cast the first mark on Duralene in 2015. Initially, the entire surface was painted in absolute black. Over the years, as the artist continued to experiment with the chemical compositions of acrylic, organic compositions of nature emerged – with dusky hues of green, brown, and red. Ultimately, as the earthy textures become dense, Mukherjee cut across each painting with a void, a sphere later cast in delicate shades of blue.

II. Limits of Nature

This abstract vocabulary must be grasped in close relation to the materiality of each work; for instance, with an unparalleled technical rigour, Mukherjee now pushes his painterly limit into the realm of sculptures. Here, material is no longer constrained as a medium or metaphor, but rather, transforms into an active agent within his process of making, and subsequently, into our ways of seeing. And woven into his approach to materiality, lies our paradoxical (but inevitable) relation to nature.

Sandeep Mukherjee, Treeskins, Installation View, Acrylic and acrylic ink on hand molded aluminium, 6 Panels, 6 x 4 ft each, 2023

In Treeskins, colossal sculpted forms – that echo dense tree barks – float weightlessly from above, eerily suspended mid-air. Their roots have vanished, assuming an afterlife, haunting a threshold of the gallery. Composed of 6 life-sized aluminium panels, Treeskins is a modular installation – which emerges in different forms, each deliberately responding to the space it occupies. For instance, in a former iteration at The Kitchen, an avant-garde institution in New York (2018), Mukherjee arranged his ‘sculpted paintings’ into two large vertical structures – consciously torn apart, separated, and at an anxious distance from one another. Curated by The Racial Imaginary Institute (TRII), in this exhibition, Treeskins morphed into a fierce witness of racial violence, as noted poet and curator Claudia Rankine observed: “ [the] sculptures of the bark of trees explores the history of lynching without employing black bodies.” [2]

In their current iteration at Project 88 (2023), all 6 metal panels gather to resemble a fragmented, even entangled, but interconnected forest; a visual that is profoundly redolent to German-born American artist Eva Hesse’s sculptural installation Contingent (1969)

Mukherjee abstracts the human body into a singular (and perhaps even the most politically inscribed) component: the textures of our own skin. This fragile interiority attains a potent focus, even as the artwork evokes an expansive and immersive experience. For this work, the artist collided his own body upon the surface of a tree – separated by a narrow layer of aluminium, which then records (and moulds) impressions of this encounter on both sides. As a viewer, you stumble upon their striking metallic imprints, the raw ‘skin’ textures intimating conflicted pasts. From one side, earthy hues of brown soothe the eye, but as you move to the other edge, dark, vulnerable, wounded and fleshy tones erode beyond the material itself. In a sharp contrast to existing discourses on the anthropocene, Mukherjee doesn’t seek to romanticise the ‘boundless’ planetary in relation to human dystopia. Out here, nature is human: mortal, split, violent, often grotesque, but at times, arrestingly beautiful in its imprecision.

III. Limits of Utopia

Sandeep Mukherjee, Cones, Acrylic on aluminium, 48 x 48 inches, 2023

Mukherjee’s geometric forms bear a striking resemblance to the Italian Futurist artists of the early 20th century; for instance, the luminosity and composition of Cones appears as an echo of Gino Severini’s Expansion of Light: Centrifugal and Centripetal (1913 – 1914), whereas the kinetic movement inscribed within Mukherjee’s abstraction corresponds to Giacomo Balla’s probe into the dynamism of (technocratic) speed, especially seen in Abstract Speed + Sound (1913 – 1914). For the Futurists, movement became synonymous with speed, and geometry as the lexicon of a ‘pure’ industrial modernity, a utopia without the burden of history. But their vision – or fantasy – was short-lived; this unbiased ‘objective’ technology of future utopia soon revealed a destructive potential. In a similar vein, Mukherjee’s work marks a critical departure from the Futurist manifesto – despite the apparent visual correspondence – for he doesn’t negate dystopic and nostalgic edges embedded into the very making of a utopic imaginary. Here, each surface moves in and against time. Mukherjee doesn’t foreclose history as his textured layers hold traces of our past – marks that stain, even crumble, but are indelible.

Sandeep Mukherjee, Valley 2, Acrylic and sand on aluminium, 48 x 74.5 inches, 2023

The (constructed) dichotomy between apocalyptic ruins and Futurist idealism dissolves into a piercing snapshot of contemporaneity in a flux; for instance, Valley 2 begins with prismatic hard edge lines propelling towards a stable vanishing point, but an unexpected corner shatters, exposing darker tones and disintegrating asymmetric structures in the same frame. There’s a surreal – otherworldly even – beauty in Mukherjee’s rendering of such distortion, for its surface is reminiscent of an unknown galaxy inside a sci-fi universe. Out here, an enigma persists as you strive to decode each artwork, for the artist deliberately abstracts familiar forms to distil their core, a sensorial texture that resists signification or language. Rankine conclusively notes: “Mukherjee’s vigilant and detailed regard of the natural world inevitably created interest in the structure of things – how things are connected, how their forms repeated, how structures held together and ultimately how preconceived structures could be translated into drawing. The drive was, in part, to find the mystery that resides within the form.” [3] And in this interstice, Mukherjee draws us into the necessary gap between language and meaning – for each lexical edge transforms into a space of possibility.

_____________

[1] Marc James Leger. Vanguardia: Socially Engaged Art and Theory (Manchester: Manchester University Press): 21.

[2] Claudia Rankine “Bleached racists and lynching trees: the show that’s targeting white supremacy” The Guardian. August 10, 2018.

[3] An excerpt from Claudia Rankine’s forthcoming monograph on artist Sandeep Mukherjee.