When the wind blows. Quotidian objects of domestic use – table fans, chopping boards, kitchen mixers, synthetic packing material – take on the semantic and material qualities of drawing, photography, and sculpture to chart conceptual routes between drawing and photography, photography and sculpture, sculpture and installation. Parts of appliances, even those that have outlived their quotidian usefulness and have now transformed into urban debris, are recovered and reinserted into fantastic imaginary topographies.

As such, the appliances that repeatedly appear in Prajakta Potnis’ work belong principally to the space of the kitchen – that laboratory-like space where otherwise indigestible vegetal and animal flesh are routinely processed, reshaped, and cajoled into forms appropriate for human ingestion. In part, Prajakta’s engagement with the gastronomical emanates from an ongoing interest in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the apocalyptic imagery of the mushroom cloud invoked by the explosion of the atomic bomb percolated into all aspects of cultural and intellectual production. Steadily and insidiously, military expertise seeped into the space of the modern home through the invention of kitchen appliances such as the microwave oven, an appliance whose technology derived from radar experimentation during the Second World War. The Second World War’s radar experimentation, of course, can be most readily associated with the ability of bomber airplanes to annihilate civilian populations with precision. The disturbing intimacy between annihilation and ingestion implicit here are explored in Prajakta’s work, as are the nebulous demarcations between the internal and the external, the private and public.

In diction and tenor, When the wind blows builds upon her 2014 solo exhibition at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, where she revisited the now historical American National Exhibition, which had opened in Moscow in 1959. It is here that the famous Kitchen Debate between the US Vice President Richard Nixon and the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev erupted in the kitchen of an American model house over the relative merits of capitalism and socialism. Staged amidst RCA Whirlpool robotic dishwashers, electronic kitchen aids powered by military technology, and canned food, the seminal debate had served to project the kitchen onto the Cold War’s terse political terrains. In sifting through the archives of such historical intersections between the political and the domestic, Prajakta simultaneously opens up porous passages between contemporary constructions of interiority and new fictions of exteriority.

Prajakta Potnis, CAPSULE 5, Digital print on Archival photo rag paper, 57.5 x 85.5 inches, 2016

Prajakta Potnis, CAPSULE 5, Digital print on Archival photo rag paper, 57.5 x 85.5 inches, 2016

Intrinsically, Prajakta seems to figuratively grasp the porosity of the private and public – purported intimacy and ostensible alienation – through scale. Consequently, the cavernous but comparatively miniature interior freezing chambers of the refrigerator – that seemingly ordinary apparatus for food preservation – transforms into vast landscapes with gigantic architectural forms. If we can take the diminutive cavities of the refrigerator as a metaphor for interiority as the hallmark of bourgeois subjectivity, then its magnification to gigantic proportions begins to function as a metaphor for the exteriority of public life and the abstract authority of the state or that of the collective over the individual.

Magnification generates landscapes that are seemingly familiar and potentially representative. They are, nonetheless, strange, unfamiliar, and uncanny. Even as singular forms seem startlingly familiar – here the smooth oblong shape of an egg and over there the dismembered whorls of a cauliflower – they are simultaneously irredeemably unfamiliar, uncanny, unhomely.

Prajakta Potnis, Site-specific installation

Prajakta Potnis, Site-specific installation

Walls demarcate the domicile, delineating the inside from the outside, segregating the interior from the exterior. Walls separate some. Others they bring together, voluntarily or otherwise. Walls will never speak. But as such, they have the ability to bear testimony to the passage of time. Time etches tracks on its skin, tests its resilience against human or natural intervention. Do escaped memories, forgotten longings, and lost desires creep into its body to seek refuge in its cracks and crevices? Can these be retrieved if we were to peel back the surface of a wall, like separating dry chapped skin from the body? The wall, however, guards its secret well. The peeling skin bulges and projects outward, extending as it were, the body of the wall itself. The hollowed out protuberances in the site-specific installation take on the appearance of sculpture that invaginates a negative, interior form. Rendering inner and outer space visible constitutes a central component of Prajakta’s artistic practice.

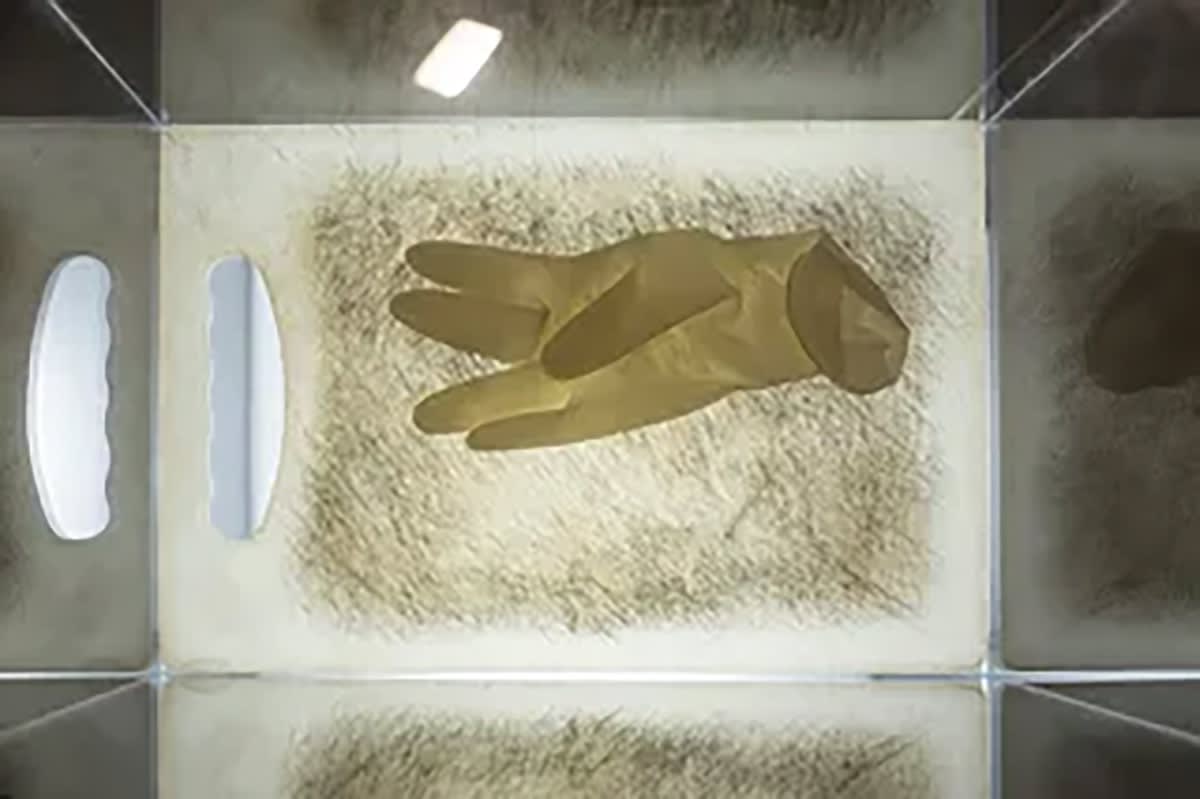

Prajakta Potnis, Chopped I, Chopping board, surgical gloves, led lights in acrylic box, 2016

Prajakta Potnis, Chopped I, Chopping board, surgical gloves, led lights in acrylic box, 2016

This spatial impulse also finds reflection in a set of plastic gloves placed upon semi-translucent chopping boards that seem to mark out the form of a human hand but in reality only encloses negative space. Speaking figuratively, the object comes to life. It infiltrates our space, as it were. In a markedly minimalist mode, the deep incisions on the chopping board take on the appearance of untitled lines on a long forgotten folio, the lead marks of the pencil only slightly fading over time. Trained in painting at the J. J. School of Art, Prajakta’s own engagement with minimalism as an aesthetic proposition extends beyond works displayed in the present exhibition. For instance, her water drawings that were part of her recent installation at the 2015 Kochi Biennale. Here, then, is another form of historical recall, this time in relation to minimalism, a particular impulse within the history of art the implications of which has never been fully worked out in the South Asian context.

Prajakta Potnis, When the wind blows, Installation view

Prajakta Potnis, When the wind blows, Installation view

At one end of the spectrum lie large format photographs with an intricately staged cinematic quality. The interior of the freezer serves as the mise en scène for monumental architectonic topographies. At the other end is a set of small drawings. Here, scale gestures towards intimacy, both in terms of the act of making and in terms of viewership. Here too Prajakta’s fantastical spatial imagination asserts itself. In the collective energy generated by a table fan and a smoking pan, the kitchen countertop takes on cartographic features. Mountainous bulges, hollowed out recesses, gorges, canyons, and smoldering volcanoes are all part of its geological features. As such, this uncanny image belongs most fully to the Anthropocene, the present geological epoch that has seen the human emerging as a significant agent of accelerated geological and climatic change. There is, of course, a certain risk involved in the work of recovering the unhomely and the uncanny, enmeshed as it is within the matrix of the everyday. But the uncanny after all, to return to Freud, is that which was once “heimisch, home like, familiar.” The pre-fix “un” of the uncanny, Freud reminds us, is the token of repression. The act of foregrounding the repressed then performs the task of reinstating that which risks being lost forever. In this foregrounding, new cultural memories rise to surface, long buried memories that haunt our history and cast shadows on our contemporary present. This, perhaps, is the ethical call of the uncanny when the wind blows.

Atreyee Gupta

Berlin/San Francisco

January 13, 2016

www.atreyeegupta.com

Berlin/San Francisco

January 13, 2016

www.atreyeegupta.com