Mozart: Which few did you have in mind, Majesty?

Directed by Milos Forman / Written by Peter Shaffer

Adapted from Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus (1979)

Mahesh Baliga cannot be hauled up for too many notes. He does not write music. Though he has been criticized for a surfeit of colours, in response to which he made Feeding the Beast (2015). A wide, red river, is flanked on the left by a man feeding a frisky swirl of black crocodiles in its flow, on the right by a small, cartoony rainbow propped on a bridge. This latter motif is modelled on a rainbow the artist saw in a reproduction of an 18th century copperplate engraving from Swiss scientist Johann Jacob Scheuchzer’s 4-volume book entitled Physica Sacra (Handbook of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1731. In the source image, a man and a dog standing before a round portal behold a rocky, mountainous landscape wreathed with two rainbows. Like Baliga’s rainbow, the round portal and the two rainbows are all patterned in coloured radial lines. These were painted in the 18th century on top of the black and white print after the book’s publication, possibly because despite being the image’s principal motifs of colour and light they were not adequately descriptive of their own colours. It is important to note that the rainbows and the portal are the only coloured motifs not just on the one page that Baliga came across. They are the only selectively coloured images across the entirety of Scheuchzer’s monumental book. Regardless of whether or not one knows this backstory, Scheuchzer’s rainbow looks overwhelmingly outdone in Baliga’s painting. For a proverbially colourful thing, it looks simply not colourful enough. This is precisely why the artist included it, as an ironic defence of his own putatively overblown sense of colour. There is, Baliga seems to argue, no such thing as too many colours.

Aside from the appending group of hand-made wooden sculptures of birds and elephants, the paintings in this current set are all in active dialogue with the chromatic potential of paint. Barring some instances, Baliga’s preferred base for paints is casein. Embraced by less than a handful of contemporary Indian artists, including Nilima Sheikh and Velu Viswanathan, painter’s casein is a laboratory-isolated non-fat phosphoprotein derived from milk. Mixed with borax it provides the binder to create paints from pigments of earth, stone, mineral, and oxide sources, occasionally limned in this body of work by the addition of gold-coloured dust or powdered pearl. The artist prepares the casein-borax base and grinds the pigments, which take the form of granules, rocks, or pebbly bits. The two ingredients are then mixed and reground to a desired smoothness. Beyond the control gained over paint consistency, the fruits of this labour for Baliga lie in the paradoxical lack of control with respect to how the paint will behave in certain cases. The fun lies in wrestling with casein paint’s chromatic muscle.

Particularly in works with layered applications of paint, fresh layers will activate previous ones and pick up their light effects as the whole compresses into one saturated surface. So even while the surface finish of casein paint is a dependably velvety matte the colours themselves appear self-illuminating. Light seems to emanate not through the paint but from it. To someone relatively new to its alchemical quirks, casein paint can become a wellspring of colour epiphanies. Baliga, who previously painted in acrylic, adopted casein paint in 2013 after producing casein-painted sections for Nilima Sheikh and BV Suresh’s mural Conjoining Lands (2013) at Mumbai airport terminal T2. He explains how its mild volatility can produce surprising effects. Depending on the base colour’s chemical provenance, applied colours could potentially alter just before they fix on the support, that is hours after they were applied. For instance, on a lead-based ground colour, as in the large casein on canvas Birth of Sea (2014), where the orange foreground extends throughout under the blue and green marine landscape to the top of the work, the applied colours gained a light phosphorescence which the artist claims was surprising when it happened, but can be mastered and internalized over time. This is the kind of heady chroma and oblique expressiveness that Baliga is consciously after, in tandem with deliberate interventions which emphasize the narrative self-sufficiency of colour.

Previous works made in oils yearn precociously for colour’s ability to become a structural component. Farming (2013) juxtaposes a vignette of his wife after a leg accident with an image of a figure sowing a field. The heavily saturated central figure is an act of painting annotated by the sower whose work, seeding a field, resembles the artist’s act of using colour to seed the picture plane with meaning. To map this process, the long horizontal strokes forming the vertical pink figure overlap a series of short vertical strokes that widen to create the pink colour field, or receding landscape.

In the concurrent Baroda Poster (2013-14), which features the statue of the Brave Boy of Dhari, located in Kamatibaugh garden, Baroda, where the artist lives, a sunset intended to be pretty ended up as a pulsing yellow-orange configuration. To the artist this approximates the visual aftermath of a blast which he claims is the tenor of normal life in Baroda outside the garden’s idyll. Below, the thin ring orbiting the top edge of the island’s compass suggests that no matter how hard he tries his hand at representation abstraction prevails. This is why the foliage remains uninterrupted by vertical struts that might otherwise support the ring which is left to free-float here, and why its contents have a hallucinatory glow. Though painted in oil, this work’s high-keyed nerviness presciently reveals how colour will fine-tune vulnerable sensations in casein works begun only a few months later.

Home (2014) came soon after. This early work in casein is a picture of the artist’s natal home in Moodbidri village, Karnataka. But the decision to lend the image the spectral character of a building in an image of Mumbai’s Zoroastrian funeral precinct the Temple of Silence came only after his mother’s death that year. That said, casein’s materiality also has a fair share in the picture’s affect. Casein is fairly brittle when dry and therefore does best on inflexible supports such as board or on well-sized canvas. A paper support such as that used in Home calls for thin applications, such that the opaque but spare layers of chalky white produced an exacting image of Baliga’s emotive goals—to create a visual parallel for the eerie but fugitive nature of his grief.

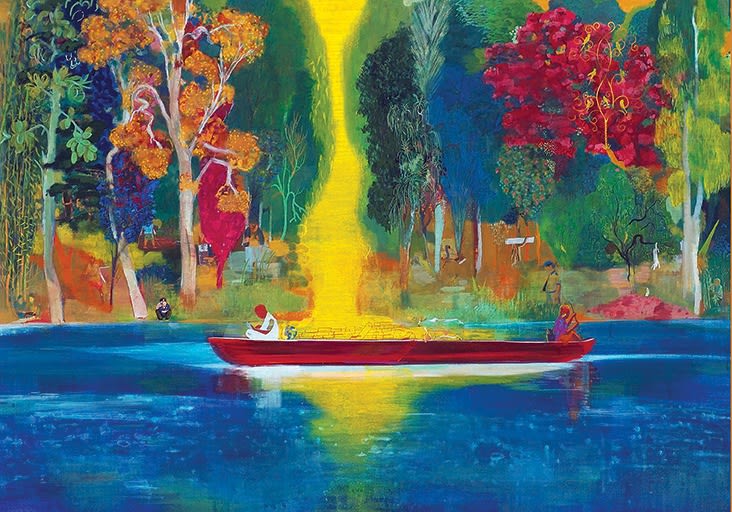

On the other end of the affective spectrum is Drift (2014), a breathlessly colour saturated landscape scene whose evocation of satiety or feeling good can become easily undifferentiated from the work itself. Spectatorship can be mistaken for objecthood. This is Baliga’s burden. In a world of art discourse where colour is pathologically equated with beauty and beauty often demotes an artist’s seriousness, Baliga has chosen to paint with more colour than many would consider wise. Yet this work’s blunt good looks are indebted less to a profusion of colour than to a single motif: the apparition rising from the scatter of books in the boat. Is it fire? Is it smoke? Is it bookish knowledge? Is it a supernatural gateway? Whatever its creed, in its capacity as both a formal and narrative interception, this elementally unclear passage of yellowness single-handedly rehabilitates the obviously blue water, the analogically green trees, the cutely improbable indigo-blue trees, the autumnally accurate reddish foliage, the naturally wan trunks of the deciduous trees, and even the must-have reflection under the boat. But note how the various, tiny figures amidst this otherwise predictable landscape are as if in a state of leisurely oblivion, inwardly turned, indifferent to the amazing—that shivering column of buttery-yellow light illuminating the air. Whether this work was meant to express the failure of the extraordinary to overturn the jaded and everyday only Baliga can tell.

Mahesh Baliga, Dead End, acrylic on marine ply, 18 x 13 inches

- Ultimately, regardless of motif or medium, painting to Baliga is a series of sometimes remote and often intimate conversations between erasure, repetition, and reapplication. Learning about Post-Impressionist Pierre Bonnard’s methods — wiping off brush strokes and applying new ones that bear the history of that erasure — was a foundational inspiration for the artist who favours visual over representational complexity. This preference partly explains his admiration for work by Indian artists Bhupen Khakhar, Sudhir Patwardhan, and Gieve Patel, who he claims produce complex images by getting straight to the heart of things, respectively through emotional transparency, perspectival collapse, and minimalism. It also contextualises the recurrence of certain motifs in his work, namely the open maws of exposed sewers familiar from his home village, the fountain shape which developed from a memory of the dome of Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, and figures in a boat. They are all pictures of what they are not. The sewer is a self-sufficient shape, no matter how gross its function. The monumental fountain is the forgetting of a building. The floating boat with its seated figures is a euphemistic icon of constraint.